A high school class started Steve Coon on a broadcast journalism and teaching career that took him from his Marshalltown, Iowa hometown, to Washington, D.C., and to cities all over the world.

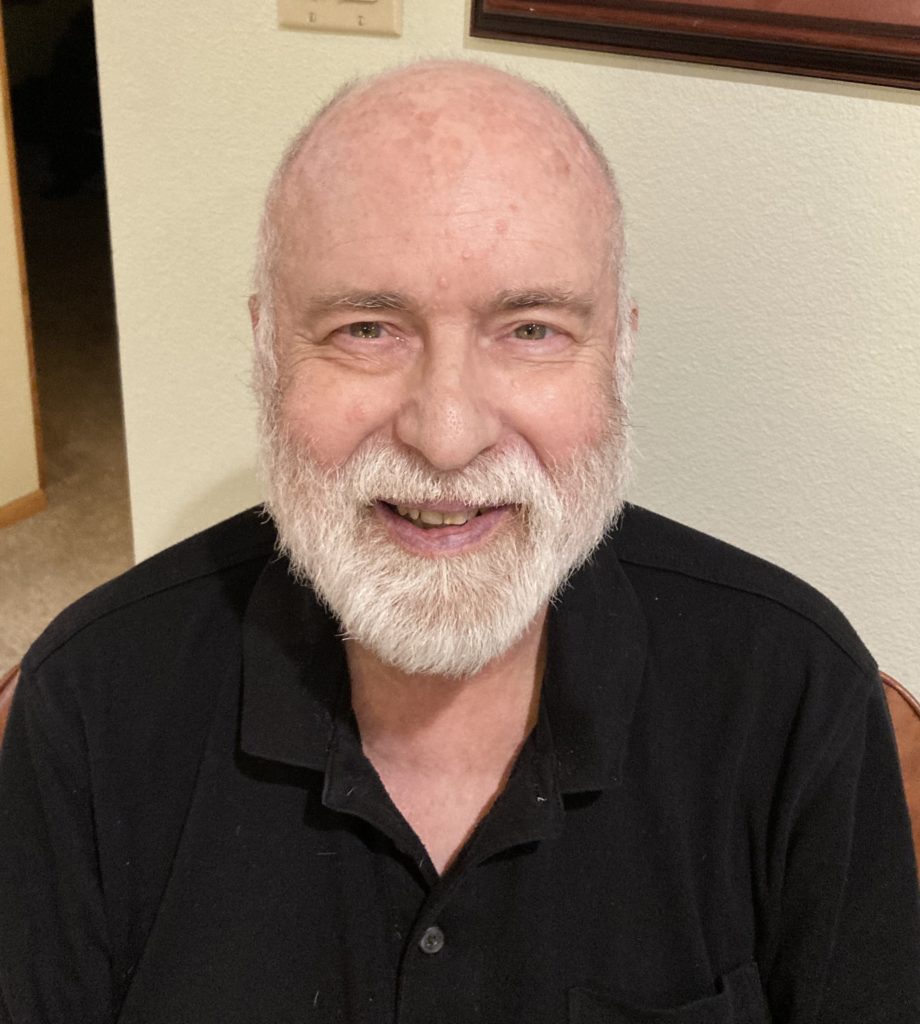

Steve is now retired from teaching journalism at Iowa State University and lives with his wife Beth in Ames. He talked about his career during an interview for the Archives of Iowa Broadcasting Oral History Project.

Below are excerpts from the interview. You can watch the entire conversation here.

How did you get interested in broadcast journalism? It started when I was in high school. I was taking a speech class and one of the things that we had an opportunity to do was once a month students in the class would go to KFJB, the hometown radio station. We had a half-hour music and talk program.

You worked at KFJB full-time for a while, then got your degrees from the University of Iowa and Iowa State University. While you were at ISU you worked at WOI radio and TV. What did you do there? WOI radio was doing gavel to gavel coverage of the Iowa General Assembly. Phil Morgan, who was the news director for Channel 5 and WOI radio, and I would go down to Des Moines. And one of us would do play by play, if I can use that description, of the General Assembly from one chamber, and the other one of us shot video and interviews of the other chamber. It made for really, really long days because at the end of that, and as the legislative session continued to get longer toward the end of the session, we would have to drive back to Ames to process the film. We were using film rather than videotape, and then we would cut and splice. So it seemed as if we were spending almost 24 hours a day working during the legislative session, but it was, in some ways, some of the most gratifying work of my career.

Then you went to Washington D.C. and worked for the Voice of America, and you’ve got an interesting anecdote about your time there. When I was at Voice of America, we would frequently get memos from the State Department. And some of them were classified, even top secret. They were basically, information, background, only the State Department was trying to persuade us to frame stories in a certain way. (For example) when you’re writing about the Panama Canal, write this or bear in mind this. So we would get these memos and the head of the Latin American desk when I was working there, would make sure that each one of us had read them, the memos and not necessarily the top-secret documents, but we read those too. After we had read the memos, he said, ‘OK, (has) everyone read this?’ And we said yes. Then he would crumble it up and throw it into the wastebasket, and we would go back to what we were supposed to be doing. Top secret memos! Too often I said, ‘why in the world is this top secret, there’s nothing in here that’s going to damage national security.’ I think someone must have run out of ink on the lower classification stamp and just said at the end of the day, ‘I’m tired. I want to get out of here. Let’s just stamp this as top secret.’

You taught at the University of Nebraska, and then made the move to Iowa State University in 1981 where you taught with the legendary Jack Shelley, the long time WHO news director who had become a professor at ISU. What was that like? He was just a great person to work with, great personality, wonderful broadcast journalist, and we who worked with him, we’re always going to be students whether we were teaching in our class with him, or sitting in the classroom with him. Final anecdote about that. My mother always considered Jack Shelley to be her broadcast hero. When he was working for WHO you could get the signal in the broadcast transmissions from WHO all over Iowa. When we were living in Mediapolis, we would listen to Jack Shelley when I was growing up. And so the year that I worked with Jack Shelley made my mother so happy that she said ‘you have reached the peak of your career. You’re working with Jack Shelley’ and I think she was right.

Another interesting and unusual part of your career was that you worked internationally to train foreign journalists. Tell us about that. I received a Fulbright scholarship in 1984 to go to Ecuador. I had an opportunity to do some teaching, and it was evening classes at a university there. That eventually led to invitations from the Voice of America’s International and Media Training Center, and then from the State Department to do short term training. I did end up going to every single continent. It was thoroughly enjoyable, extremely gratifying. (Many of the journalists) are working under terrible circumstances. By that, I mean, oppressive governments.

What do you think about the current state of journalism? I think the major problems are really at the network or national level. I think local journalists, especially here in Iowa, continue to do a good job. But they are under pressure to do increasingly more with less resources. When you have fewer staff and you have more newscasts, and you have more stories to report, it just becomes increasingly more difficult to do the kind of quality work that the public deserves. One of the expectations, which I don’t like I’ll be absolutely honest about, is that reporters are expected to blog, to post opinions on social media. I think that is a bad idea. I don’t want to know what a particular journalist feels about a particular issue. But when he or she is expected to then go and do a blog, and post observations on social media, I think you run the risk of revealing an ideological bias that in my opinion, damages your reputation and subsequently hurts the reputation of the organization that you work for. I think that’s one of the challenges.

What would you like your legacy as a teacher and a journalist to be? I just want people to think that Steve Coon was a nice person. I had a workshop with him. I was in class with him, and he taught me some things that really helped me in my career. And in my life. I’m a better person because I knew him. It’s as simple as that.

Steve continues to do reporting and video work. On his YouTube channel you can watch his commentaries, legislative coverage, political coverage, opinion pieces, sight and sound videos, and a documentary: “Clearing the Static: Herbert Hoover and the Radio Act of 1929.” He is also a past executive president of the IBNA.