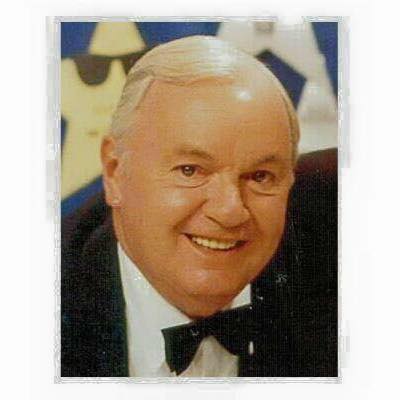

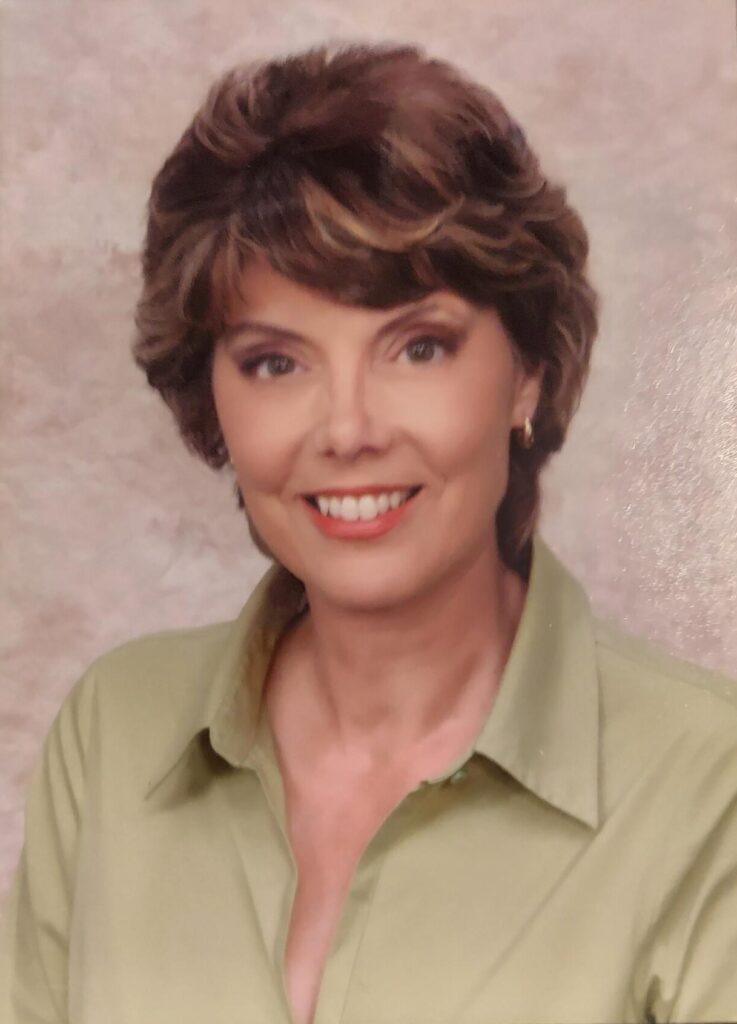

Even though she officially retired in 2024, Sue Danielson hasn’t really called it quits.

Danielson retired after a 36-year career in radio news, the past 34 years at WHO radio in Des Moines where she was assistant news director. But she says she is enjoying working part time now for the statewide radio network Missourinet. She records newscasts, does interviews, and writes stories.

Paul Yeager and I interviewed Sue for the Archives of Iowa Broadcasting’s Oral History Project. Below are edited comments from the interview. Listen to the entire interview here.

How did you get interested in radio news? I had an early interest in journalism, I think in grade school and then high school: newspaper, speech team, that sort of thing. In college, I ended up wandering into the college campus radio station at the University of Illinois, and I just loved it. I really got the bug.

After working at a station in Illinois, in 1989, you heard about a temporary job at KOEL radio in Oelwein, Iowa. I decided, sight unseen, to accept the position, and was temporary after all, (and I thought it) might be kind of fun. So I drove during an ice storm to get to Oelwein and settled into this fairly small town, so it’s a culture shock for me. I remember encountering someone in the store there, who said, ‘I hear you don’t have any furniture,’ they knew me. They knew all about me.

You left there to take a part time position at WHO radio in Des Moines. I was fairly new to Iowa, and they assigned me a story at the state Capitol. I was so embarrassed, because I had never been to the state Capitol in Iowa. I’m thinking, okay, I can see it. I know it’s over there. Just follow the dome, I guess. I was such a rookie, but it was so exciting to interview the governor and lawmakers. I mainly was a general assignment reporter for the bulk of my career, and then also news anchor. And then there was also a 15-year stint where I co-anchored the afternoon drive program with Jerry Reno .

How did you get onto that program? They needed to make a programming change, and they came up with this idea. And someone had known Jerry Reno from his past broadcasting career. He was in television, and they decided to pair the two of us and do that program, kind of a mix of news and information, interviews, a lot of severe weather, certainly, because it was afternoon drive. It lasted 15 years. So I think that’s pretty successful for radio.

There was a huge flood in Des Moines in 1993. It knocked out the city’s water plant and there was no water for weeks. How did WHO cover it? Oh, my goodness, that was such a big deal. I was planning on going on vacation the day before, and then the rain just came. The radio station lost electricity. We had to move all the equipment down to the lobby to take advantage of the sunlight and get the generators going. We worked 12- hour shifts because of just the mountain of information. This was in 1993 so consider the technology. There was just such an enormous amount of information we had to get on the air. And it was critical, because people needed their water. It was really tough for people who had lost their electricity. It was hot, and some of those folks didn’t get electricity for over a week. The city has obviously made some flood improvements since then. But that was a tough time.

How did you cover the pandemic? Salespeople and other departments worked remotely, but because we (news staff) were considered essential, we continued coming in. We tried to separate people as much as possible. I did have to work remotely when I actually got COVID for a couple of weeks, and so that was nice to have the technology to be able to do that.

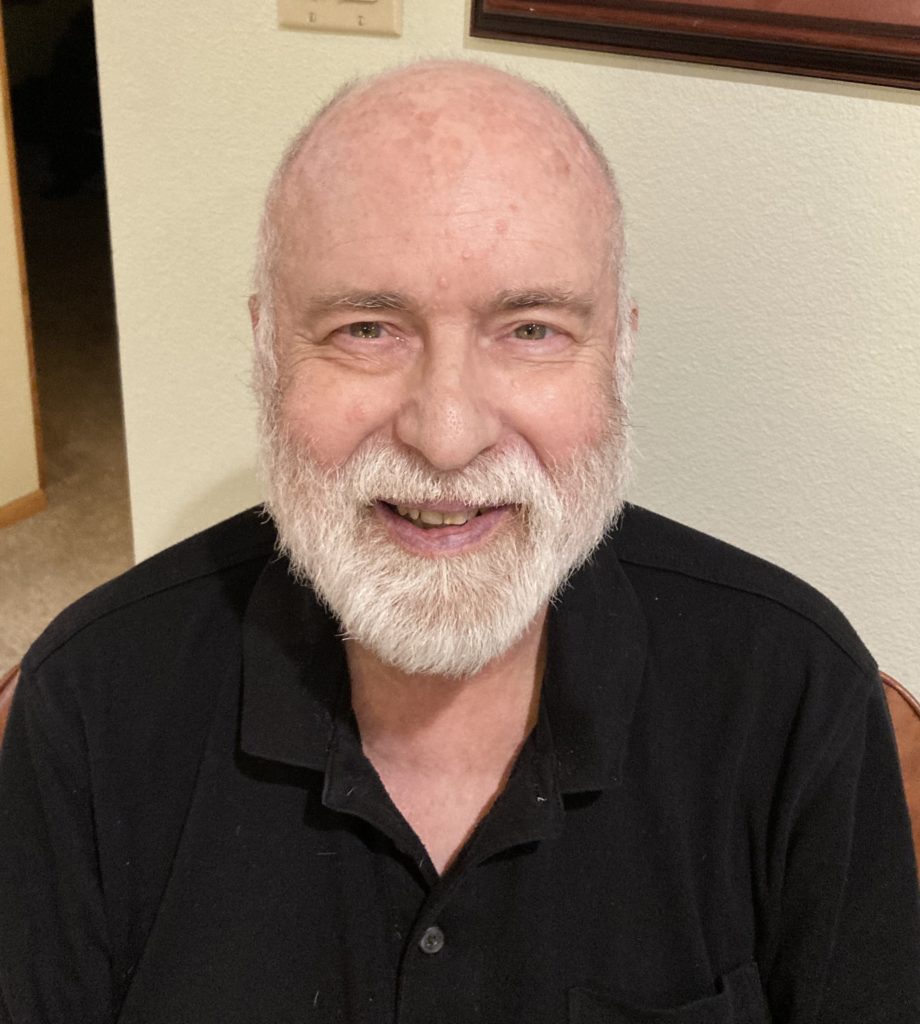

You’ve mentioned your husband Dar a couple of times (who works at Radio Iowa). What is it like being married to somebody that was, in a way, competition? We try not to talk shop at home but some of it’s unavoidable, because there are certain stories we’re both interested in. And did you hear about this today? And did you see what so and so did today? As far as competition goes, he’ll give me a hard time sometimes as, ‘Oh, I heard you finally got around to doing that story that we had last week.’

What do you tell someone who’s just starting their radio career? I hope that they feel like it’s so much fun. It’s not like working at all, because there’s always something new. Every day is different.

What’s the lead to your biography? I hope that I will be remembered as a reporter who was hard-working and fair and did my level best to inform accurately. I hope that I was able to bring some stories that lifted people up. I think those of us in this business kind of gravitate toward those happy stories, because we do so much doom and gloom.

Sue Danielson received the Jack Shelley Award in 2016. The Shelley Award is the highest honor an Iowa broadcast journalist can receive She’s also won numerous awards at the state and national level for her work.