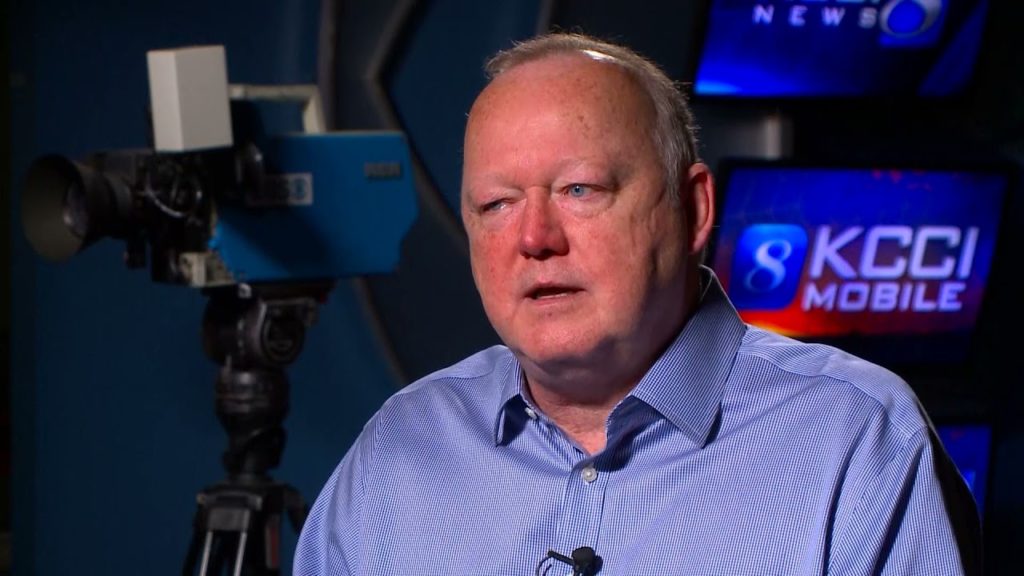

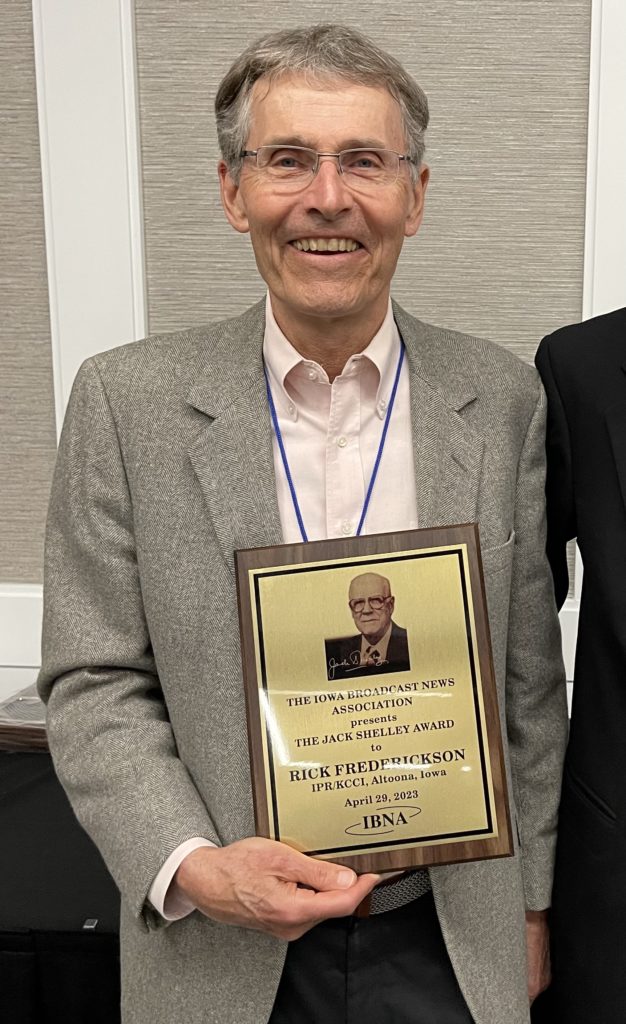

Iowa broadcast journalist Rick Fredericksen is the 2023 recipient of the Jack Shelley Award, the Iowa Broadcast News Association’s highest honor. Fredericksen’s nearly

50-year career took him from Des Moines to Vietnam, Hawaii, a return to southeast Asia, and finally back to central Iowa.

A native of Des Moines, he enlisted in the Marines in 1967 during the Vietnam war. After Boot Camp, the Marines sent Fredericksen to broadcasting school even though he never thought about journalism or broadcasting as a career. “So rather than pick up a rifle, I picked up a microphone,” Fredericksen quipped during an oral history interview for the Archives of Iowa Broadcasting.

Then for a year he was a reporter and program host for the Marine Corps Air Stations Radio and TV Section in North Carolina. Highlights included providing updates to commercial radio stations during a hurricane and covering a missile exercise in Puerto Rico.

At age 19, the Marines sent him to Saigon, South Vietnam where he was a TV and radio newscaster and war news editor with the Armed Forces Vietnam Network (AVFN). He covered military briefings and news in the field. Fredericksen said a highlight was being the lead reporter for President Nixon’s visit with combat soldiers.

While at AVFN he was involved in a controversy when he was one of seven broadcasters who were disciplined for protesting military censorship of some of AVFN’s. “When I look back now, I don’t think it was as serious as we made it out to be. I think the military has a right to restrict some news. After all, we were broadcasting in the war zone,” he said.

Coming home to Iowa

After finishing his stint with the Marines, Fredericksen returned to Iowa and landed his first job in commercial broadcasting at KRNT radio in Des Moines. After a short time he moved to TV and became a reporter at KRNT-TV (now KCCI-TV) in Des Moines.

Fredericksen worked his way into anchoring at KCCI, eventually co-anchoring at 6 pm with Paul Rhoades and at 10 p.m. with Russ Van Dyke. (Rhoades and Van Dyke were long-time KCCI news anchors, and both are previous Shelley Award winners). Here’s a newscast Rick anchored in 1976.

He spent 12 years in Des Moines then took a job at the CBS affiliate in Honolulu, Hawaii. Fredericksen’s brother lived there, and on a visit to see him Fredercksen took along a few resume tapes and interviewed for a job. Growing up in Iowa came in handy, he said, when he had to cover a blizzard in Hawaii! He had driven to the top of a volcano to cover an event when the storm hit. He ended up staying overnight during the blizzard and got altitude sickness before returning home.

Going to work for CBS

After three years in Hawaii Fredericksen was on the move again, this time to Bangkok, Thailand where he worked for CBS Radio and TV as the network’s Bangkok bureau chief. His stories were aired on all CBS news programs including the “CBS Evening News with Dan Rather,” “ 60 minutes,” “48 Hours,” and “Sunday Morning with Charles Kurault.” Vietnam was still a big story as the country recovered from the war and he went their 20 times to cover stories. Here is a story he reported for CBS.

While in Bangkok Fredericksen also started his own independent news agency and provided coverage to the Associated Press, various magazines, the BBC, public radio, and many other outlets.

Home again

Fredericksen worked for 10 years in Bangkok, then as CBS began closing its overseas bureaus he took a job as news director of WOI radio in Ames in 1995. He also served as the Iowa host and newscaster for NPR’s “All Things Considered.” While at WOI Fredericksen opened the station’s first full-time Des Moines bureau.

In 2004, the Iowa Board of Regents merged the public radio stations at the three state universities (WOI, WSUI, and KUNI) into Iowa Public Radio. He became IPR’s arts and culture reporter. During that time he launched “Iowa Archives,” a seven-year project to, as he put it, “discover historical Iowa voice and sound recordings.” He then packaged them as expanded features and one-hour programs for IPR. He retired from IPR in 2016.

Listen to Rick’s feature about restoring Trolley cars.

Keeping busy

During his retirement, Fredericksen writes articles for Vietnam Magazine and is active in the veterans community.

Fredericksen is the author of three books. “Broadcasters: Untold Chaos” is about his time as a Marine in Vietnam. “After the Hanoi Hilton: An Accounting” examines what happened to 2,500 veterans left behind in the Vietnam war. And, “Lusitania Diary” tells the story of Fredericksen’s grandfather’s emigration from Denmark to the United States more than 100 years ago. “His latest book is “Hot Mics and TV Lights” which commemorates the American Forces Vietnam Network.

Fredericksen is the winner of a Peabody Award for coverage of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests in China, and he has won several IBNA awards for his IPR reporting.

KCCI’s Eric Hanson produced a story about Fredericksen’s career when Rick retired in 2016.